Converting Climate Headwinds into Portfolio Tailwinds

Ocean Awakens Climate Week Event, held on the 1885 Tall Ship Wavertree, South Street Seaport Museum

This week is Climate Week in New York, where tens of thousands of climate and energy operators, financiers, scientists, and more, have descended upon Manhattan as the annual ‘Pre-COP’ activities officially begin. This coming November marks the 30th annual COP (Conference of the Parties), which will be hosted by Belém, Brazil. I view COP with mixed feelings. Having attended several COP sessions over the years, while it has brought attention to the relationship between what drives both emissions and economies, I still don’t think there is a clear answer around the quantification of positive outcomes. Topics, sessions and presentations are largely recycled. Many of the usual suspects at Climate Week will continue to host receptions, prepare and update slide decks, and discuss what needs to be done. All the while, emissions continue to move up and to the right (see the IEA emissions chart below).

29 years of pledges, promises, and plans. Unfortunately, at least for the energy and for climate-tilted investors, there has not been a measurable return. Globally, emissions sourced from fossil fuels continue to rise. Polarization based on ideology — not science, engineering and economics — has driven a wedge between constructive dialogue and tangible solutions. And the risk has only grown larger. Opponents point out that climate models have been incorrect in projecting climate trends as a function of changes in the chemical constituents of the atmosphere. Well, they are partially correct — the models generated by the scientific community have captured the trend correctly, but the speed at which anticipated changes are starting to manifest themselves has actually been more rapid than originally projected. So if anything, the science has been conservative, not alarmist.

On Tuesday, I spoke to a select group of scientists and investors about these challenges at The University Club of New York, at an event sponsored by the World Climate Research Programme. While the content can not be discussed as the session was held under Chatham House Rule, nothing that I heard during the day changed my mind.

One bright spot is that in last year’s COP (COP 29 in Azerbaijan), adaptation finally started to appear as more than a fringe topic, which is a needed change in direction. Will COP 30 continue to present more pragmatic solutions, or will the political dialogue overshadow the potential for real progress? Capital flows may provide an early signal. Here we outline where we are, where we might be going, and ultimately what it means for investors. How can we turn climate and energy headwinds into tailwinds?

The Current Emissions Snapshot

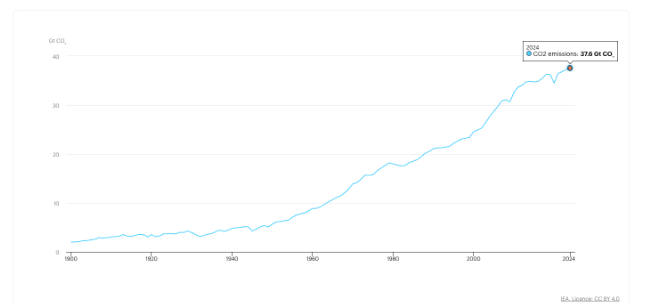

The chart below shows the current global CO2 emissions profile back to 1900. Other than a small year over year decrease in 2020, primarily attributed to changing dynamics that reshaped the global economy as a result of the COVID pandemic, total emissions continue to increase (note, CO2 equivalent estimates are likely on the low side, primarily due to conservative attribution measures for Scope3 emissions). Despite advances in efficiencies, optimization and scalable technologies, the global industrial engine continues to release more pollutants into the atmosphere, and given the projected demand requirements as a function of the ever-increasing appetite for inference and LLMs, there is no reason to believe that this trend will reverse in the foreseeable future.

Global CO2 emissions from energy combustion and industrial processes and their annual change, 1900–2023. Source: IEA Global Energy Review, 2025

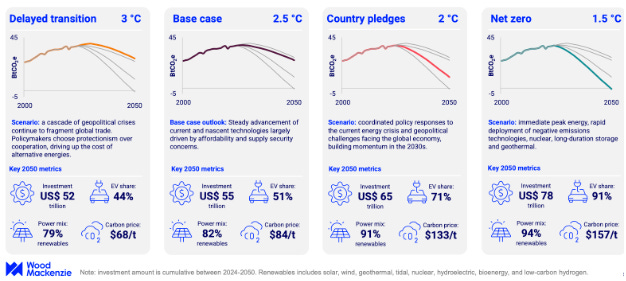

To distill the state of global emissions today, I like to use the scenarios outlined by Wood Mackenzie in their Energy Transition Outlook, released in October 2024. Simplifying the emissions scenarios, we can visualize the potential management strategies needed to ‘bend the forward curve’ so that reductions in future decades start to accelerate as a function of capital deployed today.

Emissions Pathways and Metrics Needed to Bend the Emissions Curve. Source: Wood Mackenzie

While significant increases in renewable energy generation capacity are needed to bend the curve, we still know that fossil fuel derived energy will remain as the cornerstone of production, and a true energy transition will take decades to materialize. It is worth noting the projected carbon price required to catalyze this shift — this still may be the stumbling block that stands in the way of prudent capital allocation. This is also why the framing of the global ‘Energy Transition’ should be viewed more as an evolution, and less of a revolution. The foundation of a sustainable society is built on the secure and reliable provision of energy, and rapid phase changes with respect to energy sources are (a) not feasible and (b) not constructive to long term substitutions.

Further, the brutal truth is that the 1.5° C limit to emissions that drives ‘Net Zero’ targets is unrealistic — with many scientists suggesting that this threshold is already a near certainty to be crossed. Therefore, we are collectively doing society a disservice if we are trying to frame capital deployment and infrastructure development plans around a set of conditions for a world that does not, or will not exist. So while mitigation is important, the reality investors need to begin steering their efforts, and capital, to the adaptation side of the equation. Dr. Parag Khanna and I have been vocal about this before.

The Adaptation Opportunity — From Climate Risk to Climate Opportunity

Here is just one example: Energy, unlike nearly all other industrial operating sectors, touches everything.

The future energy matrix can support multiple visions of what sourcing and distribution actually looks like, and much of this will be geographically dependent. While the forecast for the path forward might look uncertain, one reality is clear: oil and gas will remain foundational to the energy infrastructure of tomorrow. For this reason, the way in which externalities are measured and managed needs to evolve, along with how energy is generated. Relying solely on emissions indicators is inadequate for identifying the sectors most likely to drive scalable investment, deployment, and innovation toward both cleaner air and resilient, sustainable energy systems.

The opportunity now exists to build investment frameworks, that first and foremost do not embrace divestment. Problems do not get solved by excluding the levers that can drive the most change. This also means that there is an opportunity to discover long duration value through multiple expansion across small, mid and large cap companies, that capture appreciation via financial metrics where adaptation variables are viewed in line with standard benchmarks as share price, EBITDA, or earnings. Framing adaptation alongside conventional performance indicators creates a pathway for multiple expansion and sustained value creation across the energy and climate transition.

Some key points to consider:

Which countries, and suppliers and producers are most likely to demonstrate resilience amid the forces shaping the next wave of climate infrastructure investing?

Which regions are best positioned to accelerate the global rollout of distributed energy networks, embracing both legacy (oil & gas) derived production as well as emerging and scaleble solar, wind and nuclear infrastructure?

Which geographies along these emerging energy corridors stand to benefit from increased commercial activity and rising property values?

And just as importantly, which overlooked geographies present outsized opportunities today — where early investment could yield substantial returns as these trends take hold? This is not a winner take all story.

Although uncertainty remains around the future direction, appetite and long-term momentum surrounding climate-linked energy investing, one emerging theme remains clear: while decarbonization might continue to drive the Net Zero agenda for capital allocation and deployment, decentralization, adaptation and value accretion can all work together to provide investors with a unique opportunity for long-duration investment that is both economically and environmentally sustainable.

Expanding the definition of energy investment requires widening the aperture to include both upstream and downstream opportunities as central to asset selection. Viewed through the lens of decentralization, these opportunities gain clarity and relevance, highlighting how distributed energy systems carry the potential to reshape the climate-linked value proposition. Ongoing research will continue to develop and refine the long duration energy investment thesis, and in the process uncover investable names and assemble sample portfolios that are best positioned to benefit from this long game ahead of us. At its core, sustainable energy is not just an asset class — it is the financial, economical and social lifeblood of the planet.